barry s. friedman

Author, Comedian, Other Stuff

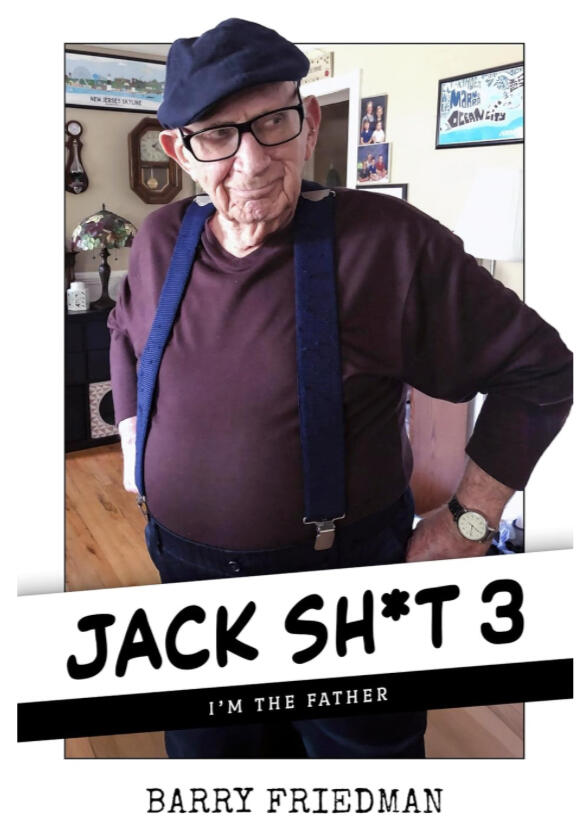

New Release

“They got some old timers here, you know, Ba? It’s a Jewish place.”

So said Jack Friedman, my father, after moving into the Tulsa Jewish Retirement Center, later known as Zarrow Pointe—but to him it was “The Hebrew Home.”

We’ll go with that.

In Jack Sh*t 3: I'm the Father—the third installment of a 4-part trilogy—we are reminded that the world is Jack Friedman’s oyster . . . or more accurately, Jack Friedman’s scrambled egg on a soft roll.

It’s always been “The Jack Friedman Show.”

Those in and around his life—the owners of “Owl Head” Bagels, the doctors at the VA, the waitresses he hoped would never know the “horror of stretch marks,” the woman he was “running with,” his daughter (who he called “that woman from Long Island”), and his sons, including yours truly—were his studio audience.

He knew his part; we knew ours.

His dementia created moments of confusion and sadness (“Where’s your mother, Ba, where’s your mother?”) but when the synapses were firing, his takes on longevity, IRS audits, bosom areas, and the possibilities of dairy products were the stuff of scholars and philosophers.

“What do they want from my life, Ba?”

“I don’t know what to tell you, Dad.”

“Don’t get so shook up. My question’s academic.”Once at the grocery store, I called to ask if he wanted me to pick him up some cheese."Cheese?" He asked. "Good question. In what capacity?"

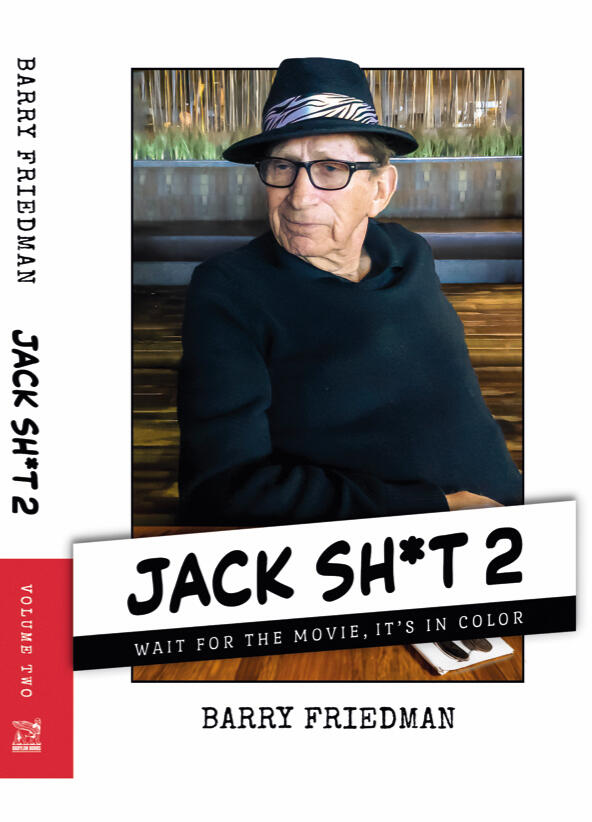

This is second installment (there will be three) in the life of my father, Jack Friedman. “Pushing 90”—that's how he described the last half of his 80s. Still in good health, he moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, albeit kicking and screaming.“He dragged me here!” he’d say, pointing to me, to those who’d ask and those who didn’t.He wasn’t completely wrong.Before, three, four times per year I’d fly to Vegas to help him find the lost icons on his desktop, change the oil in a car he should no longer be permitted to drive, organize his seven antihypertensive medicines into plastic dispensers, and occasionally find long-forgotten liquified potatoes. For all his ebullience and energy, my father was, in fact, pushing 90, and men that age have strokes and get lonely and forgetful and yell at those who, according to him, moved the roads.He needed to be closer to me. He needed someone to drive him to Panera.When the time came, I thought, better for him to die across town than in a nursing home in Vegas.His dementia when he arrived in Tulsa just visited occasionally. It was parenthetical, enlightening, and often marked by brilliant non-sequiturs. In time, that would change. But during these early years in Tulsa, Jack Friedman was still very much Jack Friedman.

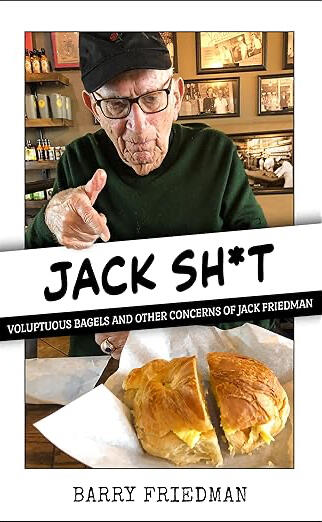

The first volume of my conversations, arguments, buffets, and philosophical musings with my father from the years 2004-2014. There was "The Mob," the survivor's group of those who buried their spouses, the bowling, the possible death of Bernie, the coupons, the long-suffering Jeannette "who buried two husbands. Did you ever? Two!" And always the toupees, many kept in boxes in the bedroom, garage, and sometimes out on the dinner table.My father, though in his 80s, thought he looked 40, and had the energy of a twenty-year-old."I was 16 two weeks ago, Ba. Where did it all go?"

Other Books

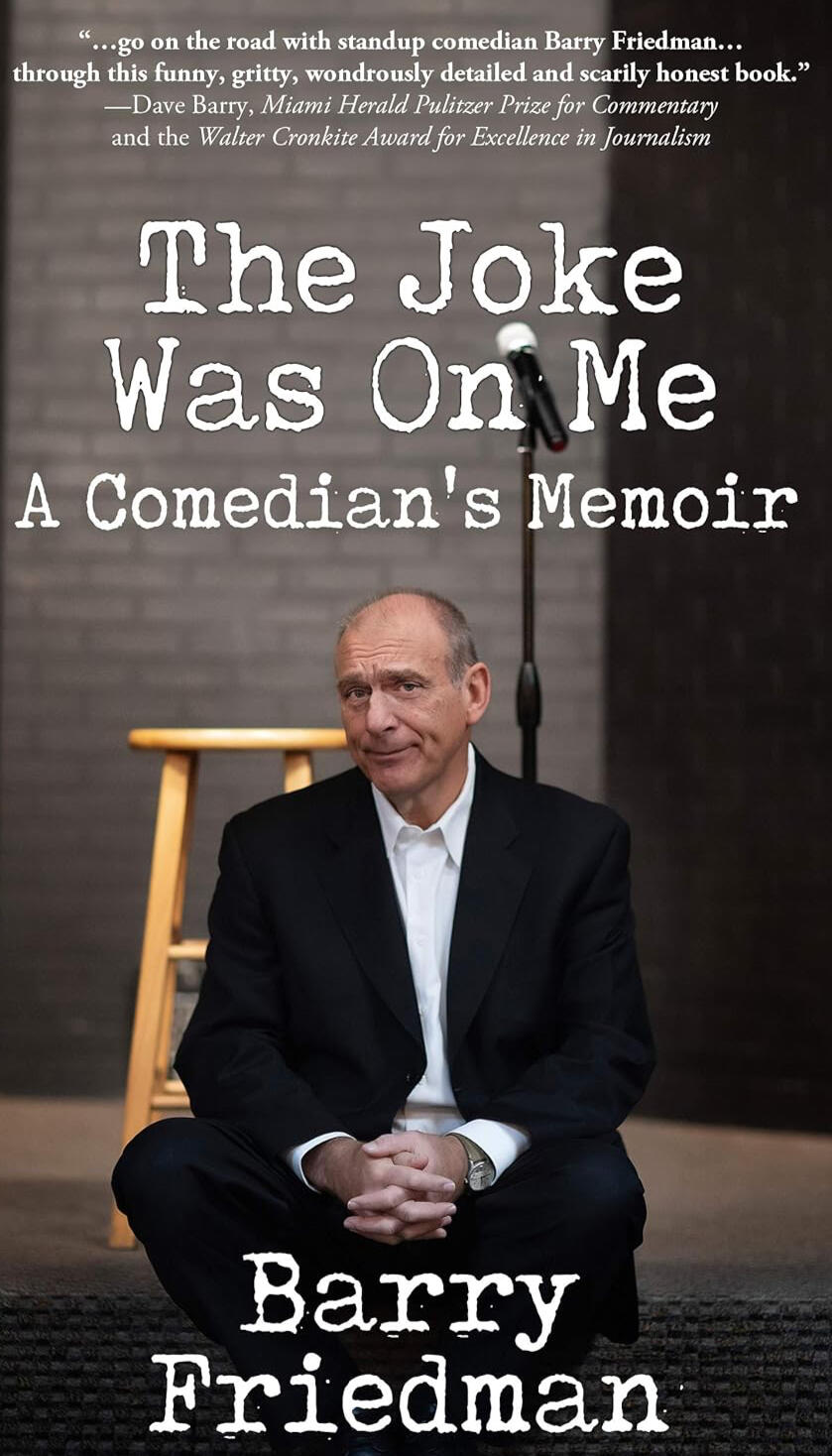

Barry Friedman, a veteran of 30 years on the comedy road, delivers another punchline on standup. Filled with garden-variety kleptomaniacs, large, rum-drinking Bahamians, bitter, glorious, troubled, and sex-addicted women with ankle monitors, loquacious drug addicts, first-time Vegas lesbians, and tall, neurotic Jews in sweaters— and these are the sane people—THE JOKE WAS ON ME is the story, his story, of laughs and love and almost fame. It’s all true—as much as comedy will allow anyway.

Jacob Fishman is miserable. His wife, Cindi, is miserable.His editor wants him to write another book.Suffocating in his own self-consciousness, Jacob decides to explore the frailties, fears, and deficiencies of his life with Cindi including, most tellingly, her desire to have a baby—and his desire not to. He creates Fishman doppelgängers, literary avatars, to see if their lives can be better than his. He wills himself to the intersection of truth, verisimilitude, and fantasy and finds himself paralyzed once there, no longer sure which events unfold in real life and which exist only in his book. Cindi, watching her life being laid bare, sees her husband as a megalomaniacal provocateur and chafes at his cherry-picking of their marriage and identities.Set in and around the University of Nevada, Reno, JACOB FISHMAN'S MARRIAGES is the story of an author’s conceit and what the creation of art excuses. It is the story of a husband and a wife and a husband and a wife—the same husband and wife. Sort of.

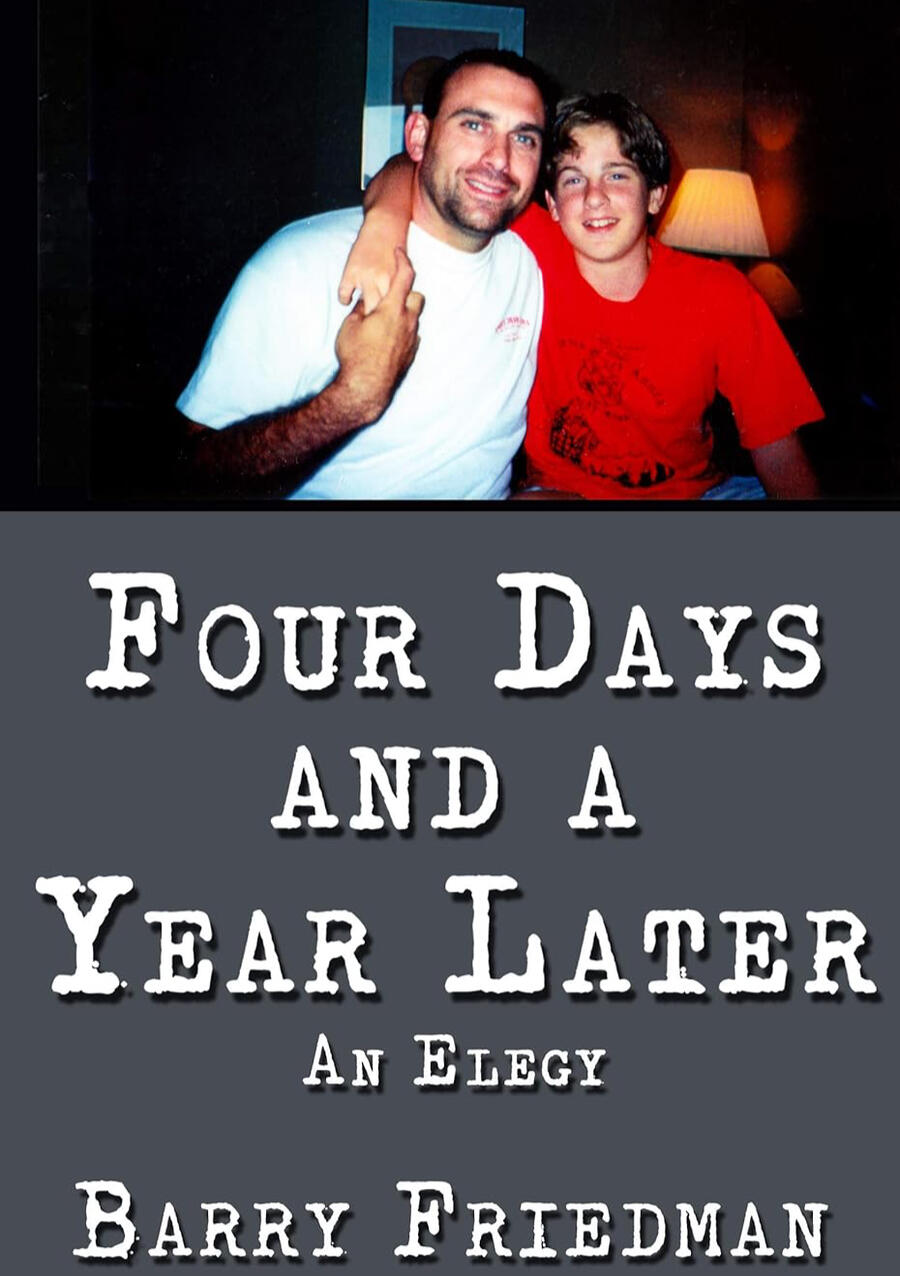

He endured every parent’s worst nightmare.When writer-comedian Barry Friedman’s son died from a drug overdose one Friday morning, Barry was devastated—but not surprised. Paul’s death had been in dress rehearsal for years. The world alternately froze and galloped after Paul was found face-down in his room. Barry had to find a way to continue, to reject magical thinking and forge a meaningful path for the future. During the following four days, Barry dealt not only with his crushing grief but also incidents ranging from the ridiculous to the profound. What follows is not a eulogy but an elegy for the son he loved but knew he would lose.

About Barry

Barry is the author of eight books — they're not all listed because they're not all that great. Barry is a standup comedian, political columnist, reporter, and his work has appeared in The New Yorker; Esquire; The Progressive Populist; MediaPost; The Las Vegas Review-Journal; and AAPG Explorer, a magazine for petroleum geologists, which is noteworthy, considering how little Barry know about petroleum geology and how he usually hurts himself filling his car with gas. Barry was also in UHF with “Weird Al" Yankovic, setting a cinematic high water mark for those who have since played (or dream one day of playing) “Crony #2” in a major motion picture. The movie still provides him with $3.76 residual checks every time it plays at a Lithuanian drive-in or when some lost soul downloads it. Barry now lives in Portugal and hates referring to himself in the third person.